SMART 2.0

In July of 2018, I joined the Center for Wireless and Population Health Systems at UCSD as a Staff Research Assistant for their upcoming SMART 2.0 research study. I became part of a relatively large (larger than I was used to, at least) team made up of public health specialists, health psychologists, and epidemiologists, to name a few. My main contribution was in the formative work to inform the development of a weight loss intervention to be tested during a biomedical randomized control trial study.

Background

The origins of SMART 2.0 go a while back, to 2009 when its predecessor Project SMART first started running. Project SMART had the same goals as SMART 2.0, to address the unprecedented overweight and obesity and their associated health risks in young adults in the United States. Project SMART proposed a multimodal, fully integrated weight loss intervention of a highly involved text messaging system, social media, personal health coaching, and SMART-developed health apps. The aim was to have a concept for an intervention that could not only guarantee significant weight loss but also real long-term behavioral change. The study ran for two years and although they found that the intervention group, compared to the control, had significant weight loss in the first year, at around the 18-month mark, there was no difference between the two groups.

The researchers concluded that there was a lot of potential here. Initial results seemed to indicate that significant weight loss with this kind of intervention was possible to achieve, but now it was a matter of figuring out what would influence people to make long lasting changes to their behavior and habits. That brings us to SMART 2.0.

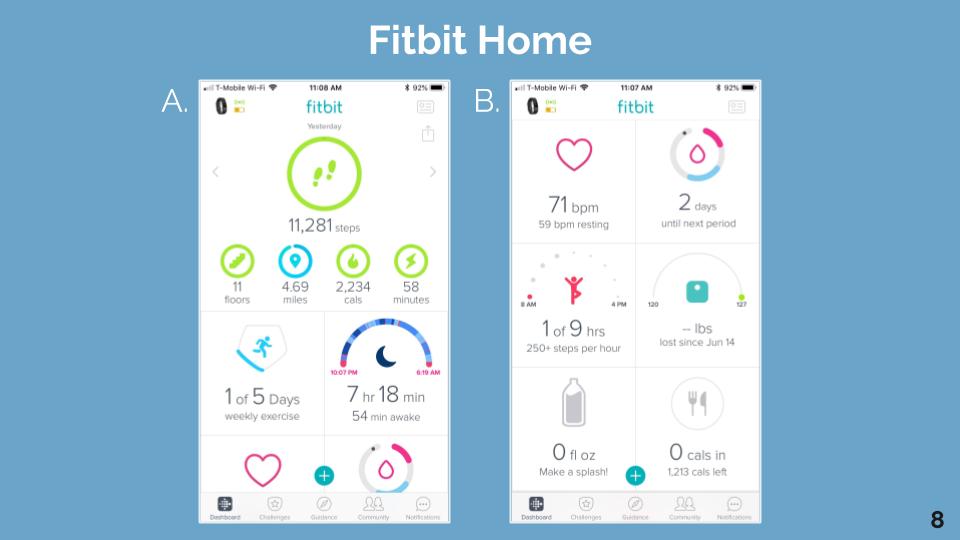

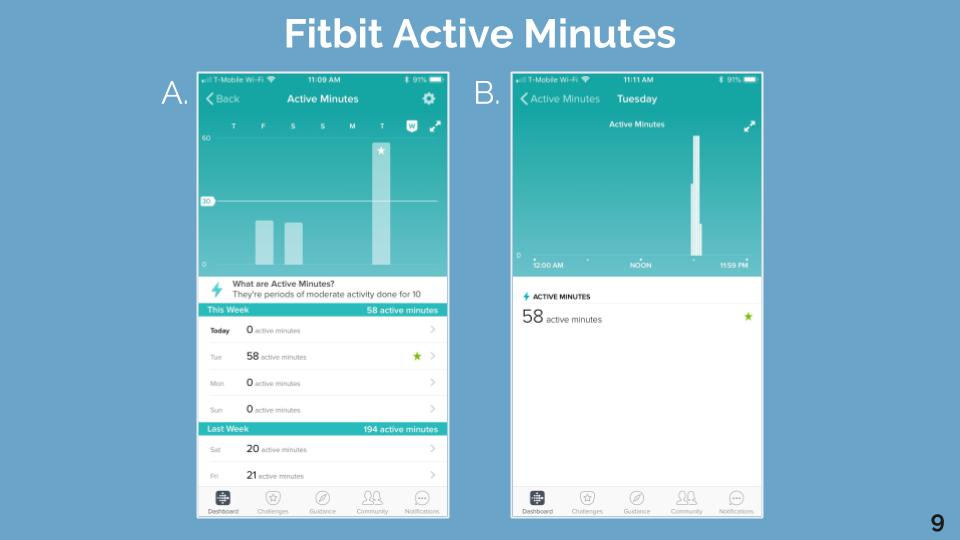

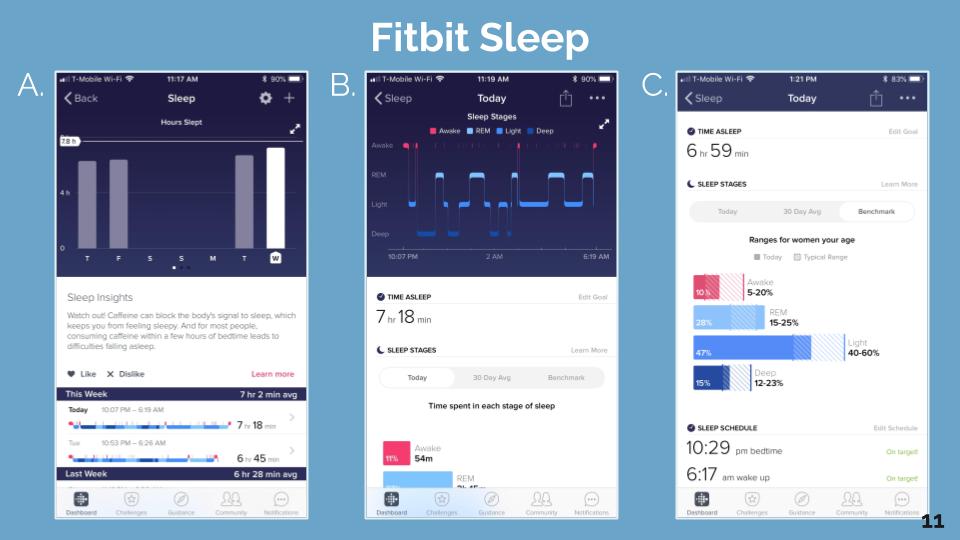

Many of the components going into SMART 2.0 come from Project SMART and related studies, as well as theory-based behavioral change techniques (BCT) and evidence-based strategies for weight management (SWM). But SMART 2.0 is different in that it has the results from Project SMART to inform itself on potential ways to enact profound behavioral changes. Before I joined the team, it was decided that SMART 2.0 would consist of SMS, social media, online group formation, personalized health coaching, and the introduction of the Fitbit, a commercial wearable activity tracker. It is the hope that by using technologies that young adults were already likely to use, the intervention would be much more effective in the long term. Additionally, this would allow the intervention to adapt to changing technologies by not having to rely on a self-developed application.

With the components decided, my job with the formative work was to help figure out how all these pieces were going to fit together.

Semi-Structured Interviews

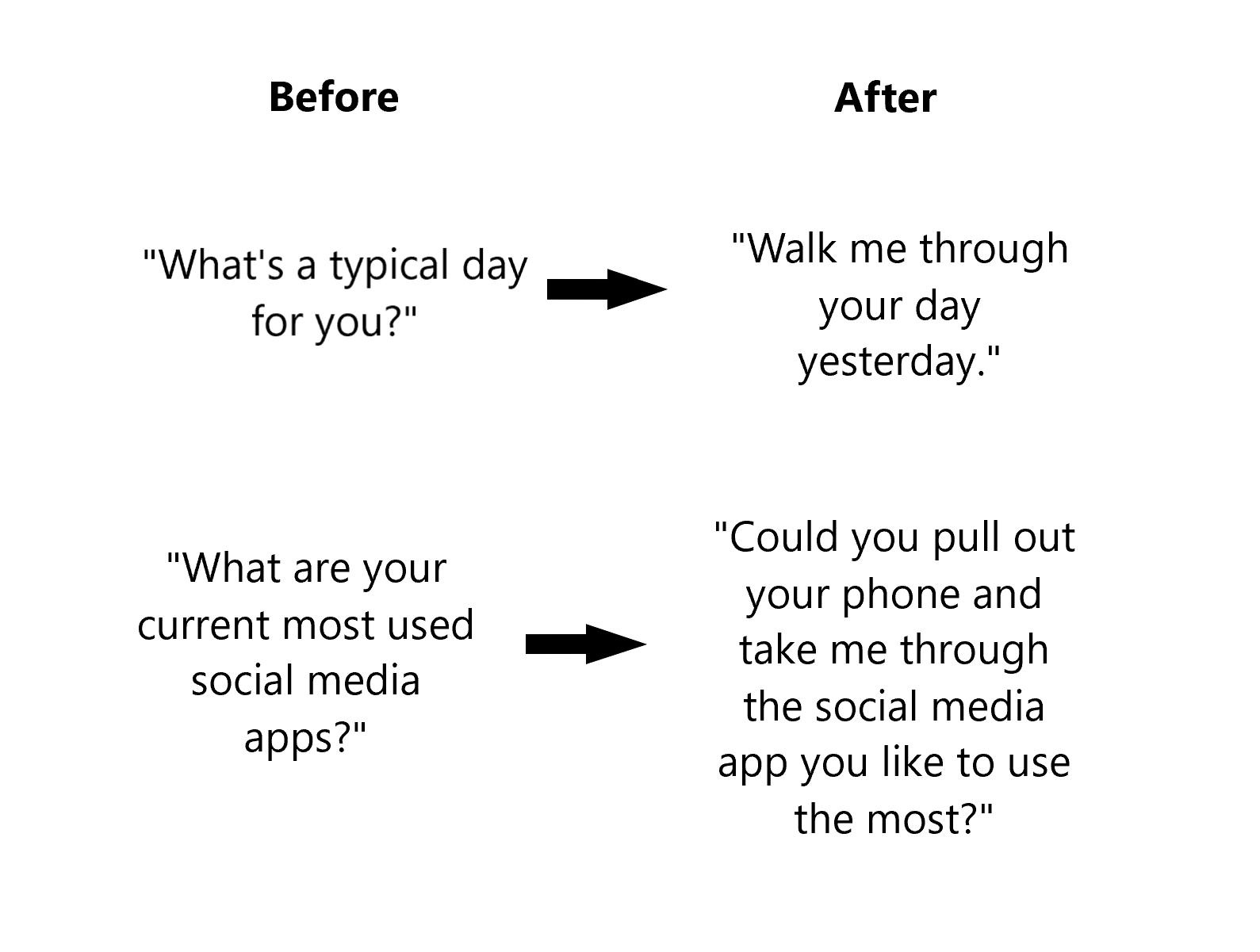

Many of the questions were already prepared when I started working. They focused around the topics and components of the intervention like current health habits, social media use, online social networks, messaging habits, and activity tracker experience. Much of my work was in rewording questions and reorganizing the interview flow to promote more expansive and honest responses. We also ran the interview protocol through a few test runs with coworkers and adjusted accordingly.

After each interview, myself and my co-interviewer would meet to discuss and write down the responses from the participant. Every week or so, we would read through these reports with our entire research team as each person would write down points that stood out to them on post-it notes. Then, over time, we would organize all the post-it notes to see what themes were emerging.

We learned that mental health was a big theme. It came up repeatedly as an important and influential component for health for most people. The intervention had already included a mental health component but it was admittedly less developed than diet, exercise, and sleep. These interview results made us reconsider perhaps taking more time to develop that component to cover mental health, managing stress, and teaching how to build resilience in the face of difficulty.

Context was revealed to be highly influential on people’s health. Family and friends have a big impact, positive and negative, on our personal decisions, even when it comes to our individual health. University campuses have incredibly disappointing options for healthy eating and often contribute to the lack of time and money students have to try to be healthier. Any health intervention targeting young adults needs to be aware and actively addressing these contextual constraints.

Despite the stereotype of young adults being on their phones all the time, it appears, at least from our interviews, that most of the time people are passively scrolling or “lurking” on social media. Most people don’t post all that often, and they are only inclined to like or comment on content with which they feel a personal connection.

Design Workshop

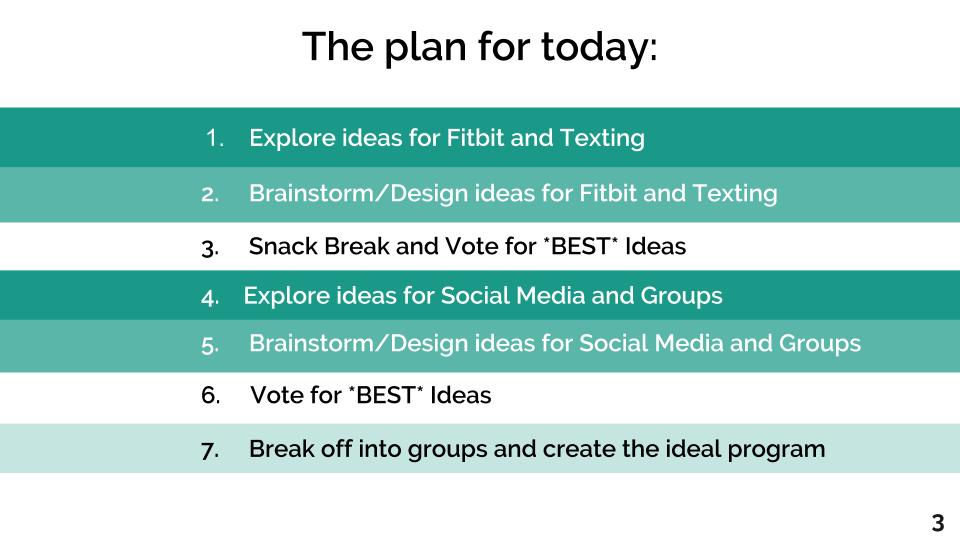

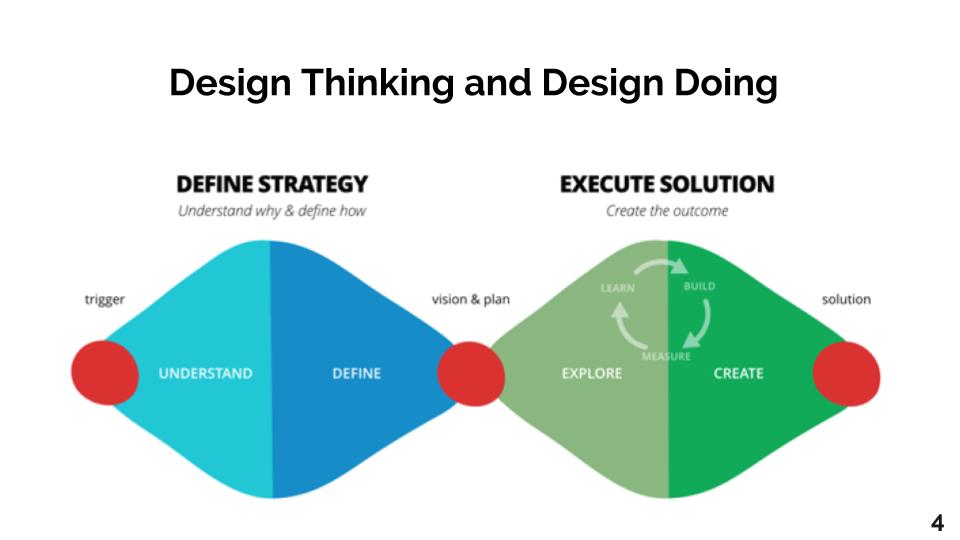

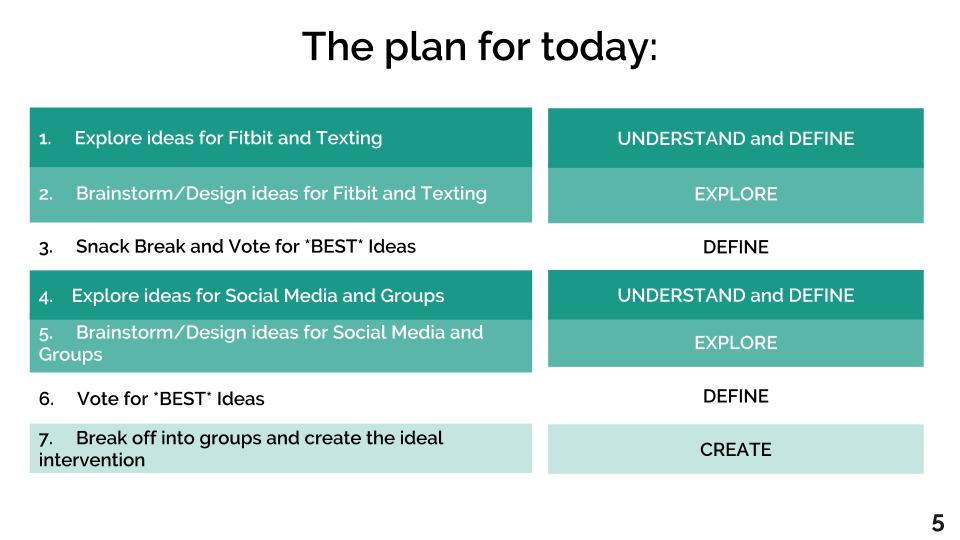

Interview responses in hand, we developed a design workshop to dive deeper into the needs of our users. This workshop wasn’t just a typical focus group, which tends towards one way interactions. Instead, we held a fully fledged design workshop, where we took users through the whole design thinking process so that they could together build components of an intervention that they wanted to see.

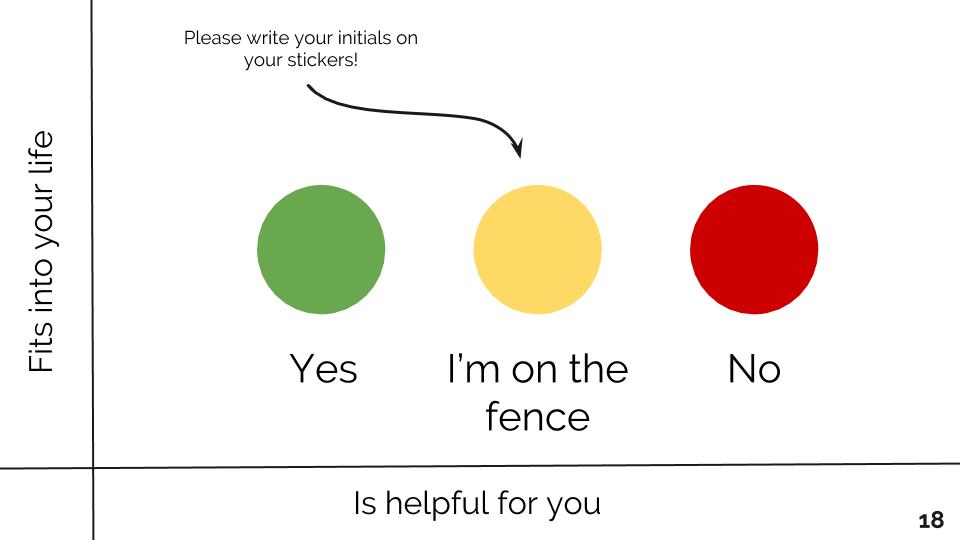

During the workshop, we also had them interact with each others’ ideas as well by having voting sessions on two different dimensions, whether the idea fit into their life and whether it would actually be helpful for them.

As a team, we reviewed all the ideas that were highly rated on both dimensions. From there, we discussed if the idea was already present in the intervention, and if not, if it was feasible to implement. Fortunately, a majority of these ideas were already present in some way in our design so far, which gave reinforcement to the designs we created from the interview responses and other background information. We found that ideas that were not implemented yet were more focused on how to make the intervention more enjoyable or informative as a whole. We took those ideas ideas into consideration, and implemented the feasible ones into our social media and online group components.

Storyboarding

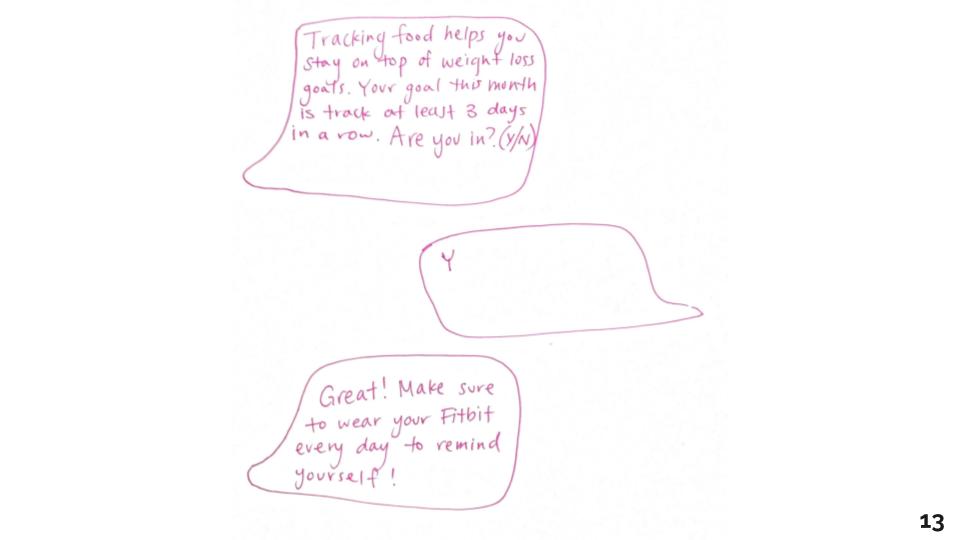

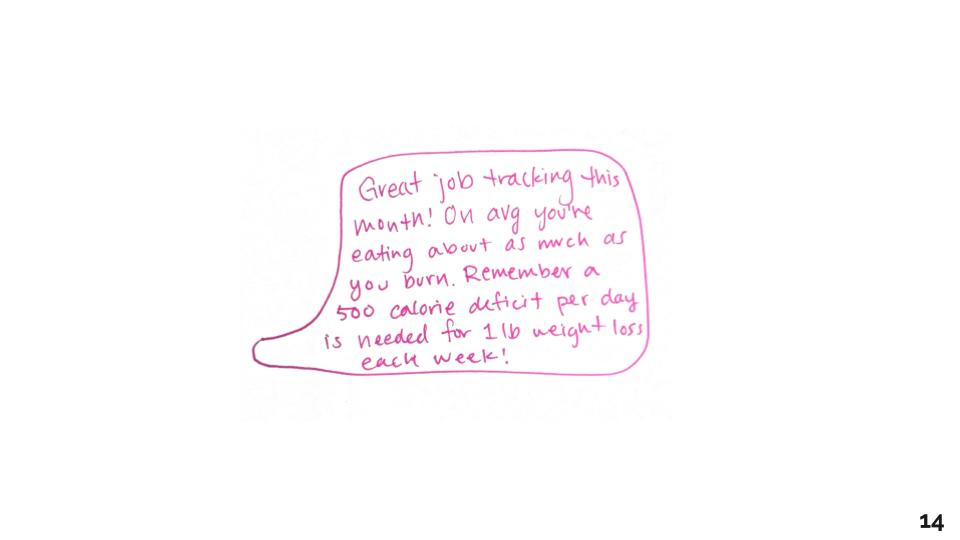

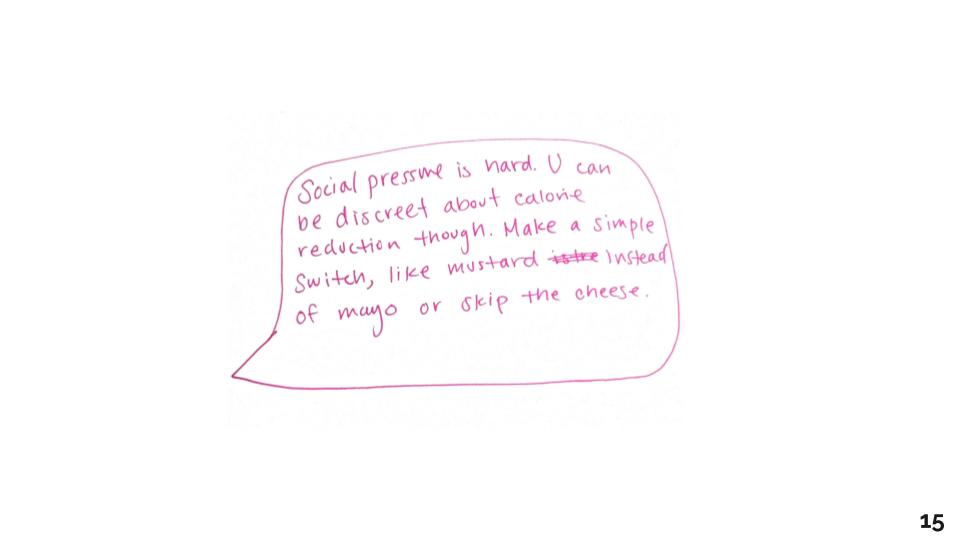

After the design workshop, the formative work was almost coming to a close. The last question we had was still, how are we going to fit everything together? We did this two ways: charting everything out and storyboarding potential users in different scenarios. Storyboarding allowed us to consider whether our intervention addressed varying scenarios like an engaged participant vs an unengaged one, someone just starting the intervention vs someone who is a year or more in, someone who is doing really well vs someone who is not doing so well, or maybe someone who’s going through a rough patch and relapsing.

I drew out all the storyboards, taking into consideration what might be happening in the online group, what texts they would get and when, and what would be posted on social media.

We would then use these storyboards as a team to bring to focus any thoughts and concerns over the total design of the intervention.

After we came to a point where everyone was comfortable with the design, we finalized each of the components to prepare for development for the study to initiate in early 2019.

Final Design Decisions

Social Media

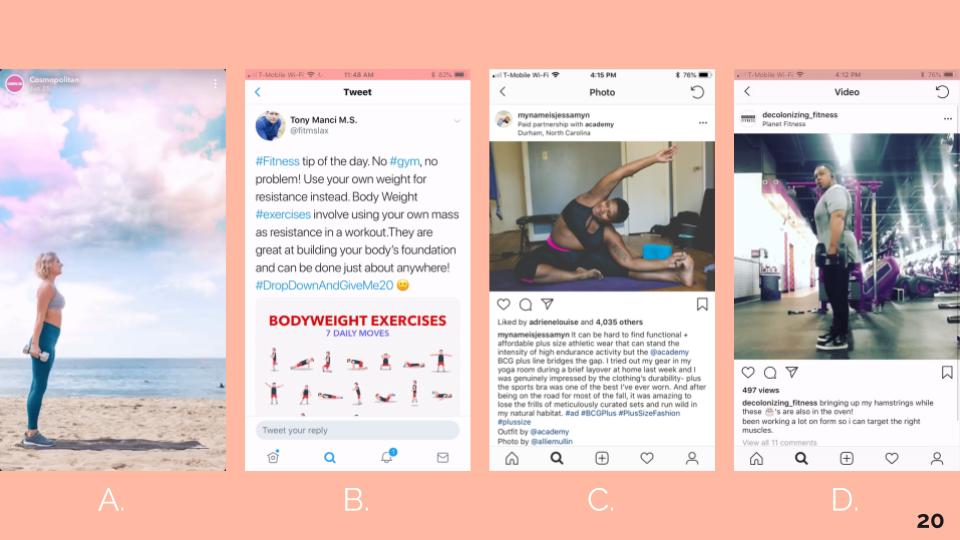

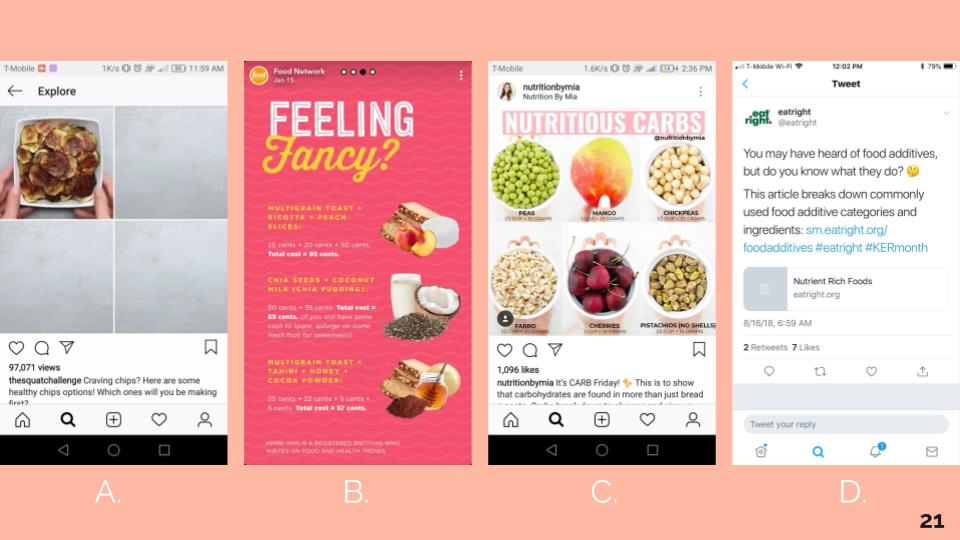

Social media content will be posted in the morning, as we learned from the interviews, many people scroll through their phones soon after they wake up. This content will be consistently visual and focus on data-backed information, teaching the basics of healthy eating and exercise, and body diversity and inclusion, as informed by the interviews. Each day will have a theme that corresponds to the SMS themes, so as to reduce an overload of information.

SMS

Both the interviews and design workshop nailed the point that text messages should be limited and highly personalized, much more than initially thought in Project SMART. Only 1 to 2 texts will be sent out a day, and they will mainly contain feedback and goal management as informed by the Fitbit data. This individualizes the texts, so as it wouldn’t make sense if anyone else were to receive the text. Text message content itself was largely based on the BCT and SWM.

Online Groups

The online groups were overall the hardest to design. We knew from the interviews that they should be smaller in size and that they should be a place of discussion and personal interaction. But in terms of how to actually design to promote this, the design input was not as informative. For this component, theories and research about group interactions from other studies became more relevant. After the initial formation of the groups, the health coach will work to stimulate group bonding and formation of a shared identity. After a few weeks, the health coach will switch to a “curriculum” of messaging a few times a week to stimulate discussion around different health themes. The eventual goal is that the health coach will gradually remove herself from the group. The groups should not depend on the presence of the health coach; they should be self-sustaining and grow into online environments where social support naturally occurs between group members.

With these finalized components, the trial study began in early February 2019 and will continue for the next 5 years. Once it begins, we will not be able to make any changes to the intervention, even if we see that something is not working as planned. Although this is different from what I’m used to with other design work, I think that letting things play out will be informative in its own right. As we go, we can identify beginnings of design breakdowns and follow the effects that trickle down. And in the end, the major breakdowns can be just as informative of future design decisions as the successes.